Ecuador is earning more goodwill with bondholders…

Ecuador is not a jaded lover when it comes to the international markets. It is doing all it can to reach a quick restructuring deal with its creditors.

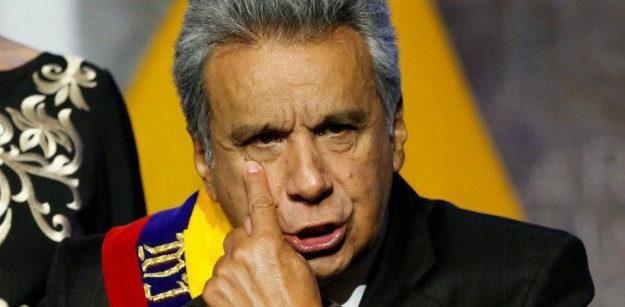

Earlier this month, President Lenin Moreno’s administration ignored public criticism from political adversaries and offered more acceptable terms and conditions on its first proposal to investors — more acceptable as opposed to terms proposed by Argentina to its creditors. One group of bondholders, which included Ashmore Group, BlackRock, BlueBay Asset Management, AllianceBernstein, and Wellington Management, supported the proposal while two other groups holding more than 25% of the Ecuadorian bonds in total and more than 35% in certain series (i.e., having the power to block a deal) rejected the offer. Although the Ecuadorian proposal did not get the necessary support, the Ecuadorian strategy must be appreciated when read in context of the restructuring process in Argentina and the greater emerging markets.

Let us not forget 2008…

Ecuador launched a successful yet peculiar debt restructuring process in late 2008 during the global financial crash. Ecuador has a history of defaults and challenges. In 1999, it was the first country to default on its Brady Bonds, which were dollar-denominated bonds created in 1989 to standardize emerging market sovereign debt and reduce the concentration of risk on commercial banking balance sheets. Named after United States Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady, the bonds were a novel idea that became very prevalent in Latin America and started the movement towards tradeable debt in emerging markets. Ecuador later restructured debt in 1995 and 2000 thus when former President Rafael Correa ran for president in 2006 with a promise to not repay the country’s debt if elected, it did not necessarily shock investors that he won.

Following his election, Correa created a national debt audit commission to examine the country’s debts contracted between 1976 and 2006 on a legal, political, and social scale. At the time, Ecuador’s Economy and Finance Minister Ricardo Patiño stated “[The audit] will consider all relevant legal, political, and economic factors, which have led to the accumulation of illegitimate debt in this country. The audit commission must also consider social and environmental damages to the local populations caused by debt. Debts which are found to be illegitimate must not be paid.”

The report ultimately detailed a series of lending irregularities and then determined some of the loans to be exploitative thereafter permitting the Ecuadorian government to default on two bonds simply because the bonds were deemed ‘illegitimate’ by the government. Following the defaults and a precipitous fall in the bond prices, the Ecuadorian government conducted a bond repurchasing program with a participation rate over 90 percent at 35 cents on the dollar. The remaining bonds were purchased by the government over several years and Ecuador returned to the market with new bonds in 2014.

Putting Ecuador and Argentina restructurings in context…

Like Ecuador, this is not Argentina’s first rodeo. When Argentina missed the deadline to pay $503 million on 22nd May this year, it marked the ninth default for the country since its independence in 1816. Creditors expected this default, but the missed payment finally set the stage and turned on the music for the creditors next show — i.e., bondholders created their committee and prepared to judge the best ‘dance’ or restructuring proposal. The most storied restructuring in Argentinian history was in 2001, which was the country’s seventh default. The legal cases associated with this default lasted 15 years and included a well-documented seizure of an Argentine naval vessel that was docked in the Ghanaian port of Tema.

Both countries could choose the same fight strategy with today’s creditors. But the cat and mouse game with assets seen in 2001 coupled with disputatious public messaging does not necessarily play well with long-term investors. There remain hedge funds in the bondholder group, but most analysts do not see the same vulture funds from the old days. Furthermore, although the causes for this default may be over-spending and bad economics, covid-19 creates the right backdrop (and ideal timing) for a debt restructuring. Covid-19 has wrecked developed and emerging markets alike, wiping out earnings at corporates, decimating economies, and stripping government coffers of cash. Thus, the argument for liquidity is clear…plus the story is more palatable with the IMF apparently keen to support. The IMF already approved $643 Million in emergency assistance to Ecuador. Lastly, Ecuador and Argentina can establish some precedent for the various ongoing restructurings (i.e., Lebanon and Zambia) and the other restructurings in the pipeline.

Ecuador’s different strategy and more pleasant attitude…

With all the similarities, Ecuador and Argentina are different and their strategies manifest those differences. First, Ecuador is restructuring significantly less debt, i.e., about $17 billion in bonds for Ecuador compared to $65 billion for Argentina. The smaller amount automatically reduces the complexity of the situation. Secondly, Ecuador’s government has a true liquidity story with its currency reserves around its lowest levels in the last two decades. As of June, Ecuador was holding about $1.2 billion in net foreign currency reserves at its central bank.

Third, toss in the reality of Moreno’s presidency. He was Vice President under Rafael Correa from 2007 to 2013 and very much part of the 2008 restructuring process in Ecuador. Moreno won a narrow victory in the 2017 presidential election as leader of Correa’s PAIS Alliance, the center-left political party, but then changed policy positions shortly after his victory. He has abandoned significant parts of the legacy of Correa by stripping Julian Assange of his Ecuadorian citizenship, allowing social movements and protests, and permitting investigations into Correa’s administration.

Now Julian Assange is incarcerated. Protests undid Moreno’s efforts to raise fuel prices. And Correa was convicted in April in absentia on corruption charges and sentence to eight years in prison. Altogether Moreno’s government trends right (with political analysts speculating if this is an actual shift away from the leftist populism and spending that has controlled the country for years). His Finance Minister Richard Martinez is also facing criticism for his quick engagement with private creditors and making previous bond payments.

Moreno’s change in policy at home with Correa’s legacy underpins his ability to be quick and different in his approach to negotiations with creditors. Sovereign debt restructurings are expected (or assumed) to be arduous and acrimonious. Yet Moreno’s administration wants to engage bondholders with a clear story on the country’s economic rebound potential coupled with a true picture of liquidity and negotiate terms within those realistic parameters. Basing discussions on liquidity is very differentiating, especially when compared to other restructurings, because it eliminates the discordant nature of other negotiations and relegates the discussion to a more detailed discussion around numbers and economic performance (and less about past public spending and a country’s ability to be good stewards of foreign capital). Yes…economic and social policies remain a debate. But, with Correa’s conviction and the internal political clean-up by Moreno’s administration, Moreno’s team has well-earned goodwill with bondholders and is building upon such goodwill with a friendly stance toward the bondholders.

Does this make a deal easier…

A sovereign debt restructuring negotiation is a sovereign debt restructuring negotiation…you cannot dress it up as anything else. It has politics, economists, (social) policy advisors, and emotions, which is a dangerous concoction for any country, yet alone a country going into an election year. That said, Ecuador’s approach and strategy makes you believe the solution is closer each day. Some political and market analysts believe a debt restructuring deal is possible by the end of August. Let us be clear…there is not the same optimism for a quick deal with other ongoing restructurings (i.e., Zambia and Lebanon). This optimism coupled with honest engagement is a success story by itself. In other words, the downturn may remind us of 2008 but Ecuador’s response surely does not. Now, let us hope that there is an agreement for the country’s situation that gets across the line with the bondholders and is palatable for any president trying to implement it (beyond Moreno’s time in office).