…The old U.S. playbook may not apply…

“Oil for Security” is dying with the changing regional security dynamics…

The original deal between the U.S. and Saudi Arabia was quite simple: The U.S. gave security guarantees to Saudi rulers and, in return, those Saudi leaders provided access to the kingdom’s immense oil reserves. The Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement signed in 1951 solidified this long-standing bilateral relationship as well as papered over ideological differences on the Arab-Israeli conflict and human rights among other things between the two countries.

Today, the Abraham Accords have cut through the old chessboard in the Arab-Israeli conflict and turned down the volume on human rights discussions. The UAE and Bahrain recognized Israeli sovereignty and brought other countries alongside them in opening business ties and trade. While Saudi Arabia has not signed the agreement, it found commonality with Israel and the U.S. in viewing Iran as the enemy.

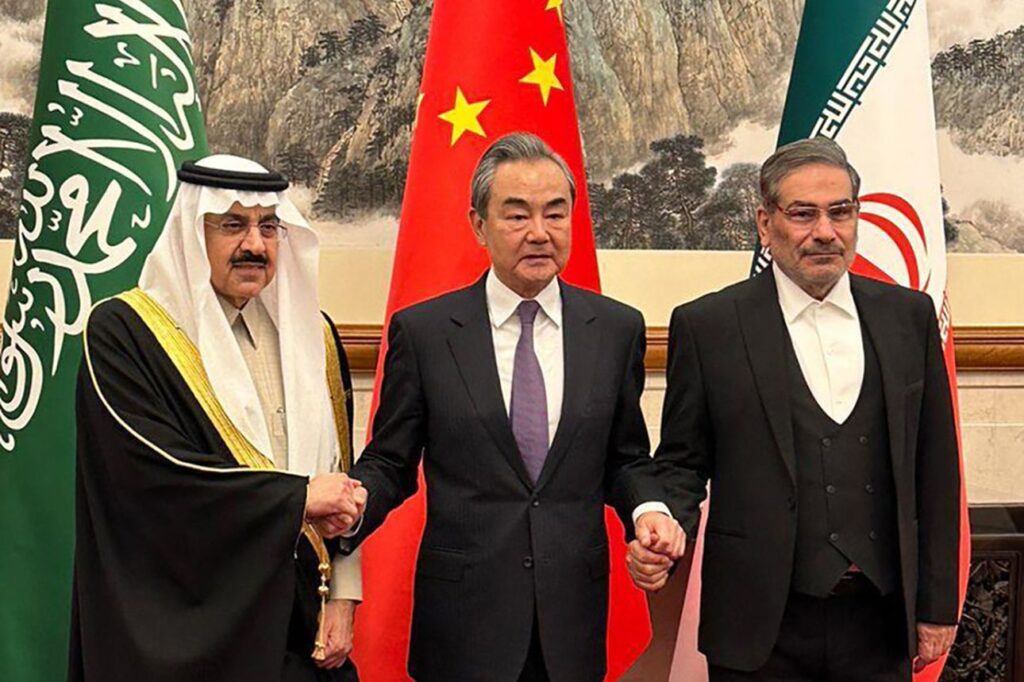

If the conflict with Iran has been neutralized with the new Saudi-Iran deal, then the alliance (or, at least, understandings) based on Iran as a common enemy will crumble or need to be reconfigured.

As a result of this agreement, Saudi Arabia and Iran can reduce their military spending in places such as Yemen (which is great for both countries)…Saudi Arabia would also like to eliminate the risk of any further drone strikes on its oil facilities (allegedly funded by Iran).

Saudi rulers will likely take comfort that, if this deal has security gaps or hiccups such as Iran developing a nuclear bomb, Israel will be watching with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu vowing to consider “all possible means” to prevent Iran from acquiring a nuclear weapon. Some skeptics would argue that this consideration is naturally built into the thinking of both the Saudi and American leaders, which ensures the Israelis remain an integral part of the region’s security balance.

Still, the U.S. will theoretically become a less relevant security partner with less bargaining power going forward…though Saudi Arabia is (unsurprisingly) looking to develop its civilian nuclear program and have (surprisingly) asked the U.S. to assist as part of a deal on Saudi Arabia joining the Abraham Accords.

Oil is still very important in 2023, especially for the U.S. and China…

The U.S. shale boom is not exactly a boon anymore to production with climate change advocates successfully shifting U.S. focus (and money) to renewable efforts. While the global transition to greener energy moves at one pace, the U.S. is attempting to lead with a faster pace of investment in renewables and reduction in carbon emissions (in particular, less oil production over time).

However, this shift in policy comes at the risk of the U.S. becoming more reliant on (or at the mercy of) Saudi Arabia and the greater OPEC+ decisions on supply and price management in the market. OPEC currently produces nearly 60% of internationally traded oil. As the argument goes, if the U.S. importance to regional security becomes less relevant, then the U.S. faces the risk of becoming more economically vulnerable (via oil dependency) to Saudi Arabia who requires U.S. security guarantees less and less by the day (while still being left with an Iran problem). According to Bloomberg, analyst surveys suggest an oil price above $80 in the coming years, which is well above the $58-a-barrel average price between 2015 and 2021.

Furthermore, China is the largest buyer of oil in the world and buys more oil from Saudi Arabia than anywhere else. Almost half of the $87.3 billion bilateral trade between the two nations in 2021 was China’s oil imports…the oil imports accounted for 77% of China’s total imports from the kingdom.

As the U.S. and the European Union continue to focus on sanctioning business with Russia and targeting Russia’s oil exports alongside other major exports, China likely sees a good business decision in strengthening alliances with Saudi Arabia (who will continue to supply oil to the country as demand grows) and Iran (who is the 7th largest oil producer).

The U.S. and Europe do not have the same problems with (nor sentiments towards) China…

The U.S. has a China problem with policy analysts conjuring Cold War analogies as the relationship quickly thaws between the two counties. U.S. House Speaker Kevin McCarthy recently hosted Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen in California as she traveled to Central America, which is the first time a Taiwanese president has met a speaker on American soil (Former Taiwanese president, Ma Ying-jeou, of the opposition Nationalist Party is currently on a 12-day trip through China).

The U.S. also recently shot down Chinese “spy balloons” which the U.S. believes the Chinese government used to survey U.S. military sites and translate such data back to China. This Sino-American tension has now become palpable in policy with the recent implementation of the CHIPS ACT, which prohibits funding under the new investment act from being used in China.

With presidential campaigns already teeing up announcements for 2024, both political parties in the U.S. are equally jockeying to be viewed as the most anti-China (some 38% of respondents to a recent survey by the Pew Research Center labeled China as an “enemy,” which is a 13 point increase from last year, while more than half described China as a “competitor” and only 6% viewed China as a “partner”).

European opinion is both less visceral and less negative. The U.S. and Europe may align on Ukraine and Russia but there is a gap between the two sides on China. French President Emmanuel Macron, in his recent visit to China, stated opposition to calls to decouple from the world’s second biggest economy. He will find support from other European countries – China, for example, was Germany’s biggest trade partner for the seventh year in a row despite some uproar in Berlin to reduce German trade dependence on China. In general, the European Union is very reliant on its trade relations with China with the country being the third largest partner for European Union exports of goods and the largest partner for European Union imports of goods in 2022.

Lastly, despite political warnings at a sovereign level, U.S. businessmen are not exactly walking away from China (or Saudi Arabia), leaving the U.S. government to navigate the politics on a national level while American companies ‘do their own thing’ on a business level. Chinese and Saudi leaders could happily live with an arrangement of less U.S. government influence and security interference if it has minimal effect on U.S. business investment (though the CHIPS Act obviously demonstrates U.S. officials’ willingness to interfere in markets when they deem necessary).