…History will not be kind to those who fail to act decisively…

This was originally published by The Washington Times.

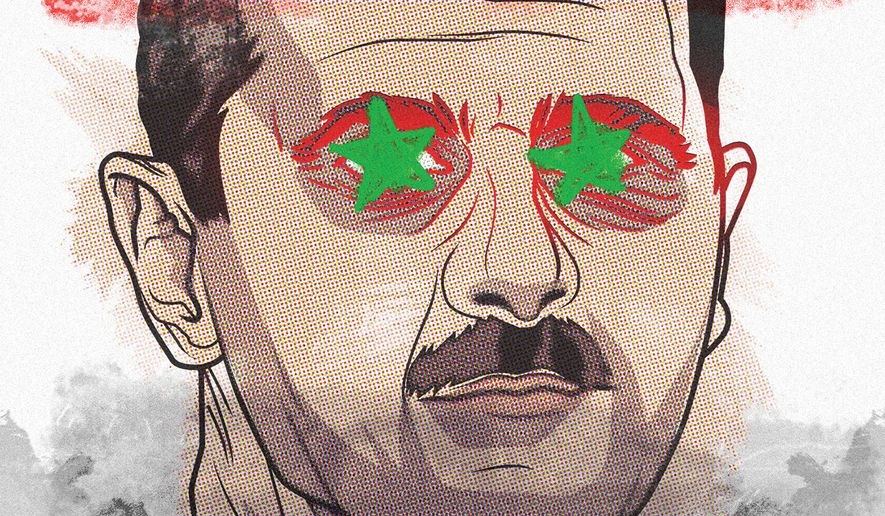

The dramatic fall of Syrian President Bashar Assad marks a watershed moment in the tumultuous history of the Middle East. Mr. Assad’s regime, sustained for years by the external lifelines of Russia and Iran, finally crumbled under the weight of its contradictions and the enduring pressures of civil war. For the United States, his fall underscores critical lessons about our foreign policy failures and raises urgent questions about the road ahead.

1. Obama’s ’red line’ fiasco proved a catalyst for prolonged suffering.

President Barack Obama’s 2013 declaration of a “red line” against Mr. Assad’s use of chemical weapons was supposed to be a moment of moral and strategic clarity. Instead, it symbolized indecision and ineffectiveness when the U.S. failed to follow through.

This hesitation sent a message to Mr. Assad and, more importantly, Russia and Iran, that American threats lacked credibility. Their subsequent intervention prolonged Mr. Assad’s survival and turned Syria into a battlefield for global and regional powers.

The swift collapse of Mr. Assad’s regime in the absence of Russian and Iranian support highlights how fragile his hold on power was all along. A resolute and timely U.S. response in 2013 could have changed the course of Syrian history and spared millions from the horrors of war. Mr. Obama’s legacy in Syria will remain a cautionary tale of what happens when rhetoric outpaces action.

2. Biden’s slow foreign policy leaves Israel and Turkey steering the ship.

As Mr. Assad’s regime fell apart in a matter of days, the Biden administration has been cautious to approach the microphone (or speak with authority). This vacuum of American initiative or even voice allows regional powers such as Israel and Turkey to dictate the terms of Syria’s future.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s proactive strategy — including precision strikes on Iranian targets in Syria and swiftly moving troops into the buffer zone in the Golan Heights in the aftermath of Mr. Assad’s fall — will outpace Washington’s slow-moving policy apparatus.

Meanwhile, Turkey’s maneuvers in northern Syria, particularly against Kurdish groups, reflect Ankara’s ability to pursue its agenda without significant U.S. oversight. The Biden administration has yet to articulate a cohesive strategy, leaving the U.S. playing second fiddle to regional actors focused on shaping the post-Assad landscape in ways that may not align with American interests.

3. The battle for Syria has just begun.

Mr. Assad’s fall does not signify peace for Syria. Instead, it starts a new and perhaps more complex conflict. The Islamic State group, emboldened by the power vacuum, is already said to be resurging. Kurdish groups, including the People’s Defense Units, or YPG, and the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, are scrambling to secure their position against both IS and a potentially aggressive Turkey.

Ankara’s opposition to Kurdish autonomy complicates U.S. efforts to support its Kurdish allies, which were pivotal in the fight against IS. A Turkish-Kurdish conflict could undermine regional stability and inadvertently strengthen IS. The U.S. will need to balance Turkey’s NATO status with the need to protect Kurdish forces — a dilemma that risks alienating both allies.

4. Trump’s noninterventionist doctrine finds vindication.

President-elect Donald Trump’s insistence in the last couple of days that the U.S. stay out of Syria’s quagmire now seems prescient. Mr. Trump’s critics often deride his reluctance to engage in regime change or deep military intervention as isolationist. But Mr. Assad’s overtures in the last few days to the West, widely viewed as desperate and insincere after the rapid fall of his regime, vindicate Mr. Trump’s statement: “This is not our fight.”

The chaos following Mr. Assad’s fall will demonstrate the wisdom of restraint: Syria remains a deeply fractured nation, and any attempt at nation-building would likely be futile and costly. The battle between IS and Kurdish forces for power will raise both the financial and human costs of nation-building.

5. Russia and Iran are diminished, creating both opportunities and risks.

The weakening of Mr. Assad’s key backers — Russia and Iran — has reshaped the Middle East’s power dynamics. Russia, bogged down in its war in Ukraine, was unable to maintain its military and economic support for Mr. Assad.

Iran, meanwhile, has been battered by relentless Israeli operations targeting its assets in Syria, Lebanon and beyond, including the killing of Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah. While the diminishing influence of these adversaries creates openings for the U.S. and its allies, it also leaves a dangerous void. The absence of Russian and Iranian control could lead to greater instability, with extremist groups and competing militias vying for dominance.

Going forward without Assad

Mr. Assad’s fall offers a moment of reflection for U.S. policymakers. Mr. Obama’s failure to enforce his “red line” set the stage for years of prolonged conflict and suffering. President Biden’s slow response in the foreign policy realm has ceded foreign policy initiative (and power) to Israel and Turkey, exposing a lack of strategic vision from the United States.

In contrast, Mr. Trump’s call not to entangle the United States in Syria’s complexities now appears farsighted. He was the major voice on the issue as the Biden administration slowly developed a view.

As the Middle East grapples with the aftermath of Mr. Assad’s regime, the U.S. must revisit whether it will continue to watch from the sidelines or reassert itself (at least verbally) as a shaper of regional stability. The stakes are high, and history will not be kind to those who fail to act decisively.